Erik Eisele

Master of Policy, Planning & Management

USM Muskie School of Public Service

May 1, 2020

Table of Contents

- Statement of Professional Goals & MPPM Program Goals

- Professional Resume

- Artifacts of Work

- Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series

- PPM 615 Heifetz Critical Analysis

- IDAC Student Fellow Letter to University Leadership

- PPM 560 RSU21 Racism Crisis Analysis

- Letter-to-the-Editor in the Portland Press Herald

- AntiracistUSM.org and Student Organizing/Support

- Richard Rothstein Color of Law Lecture

- USM President’s Email Letter Regarding Campus Incident

- PPM 610 Media and Democracy Critique

- Anti-Racist Practice Group

- USM Common Read

- Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series

- Conferences, Talks, Workshops

- Reflective Essay

Statement of Professional Goals

My goal upon entering the Muskie MPPM program was to build the skills to succeed in complex organizational environments. I was seeking a stronger foundation in strategic planning, organizational development, project management, relationship-building and facilitation, as well as the leadership skills necessary to support consideration for advanced positions with high-performing organizations (public or nonprofit) dedicated to supporting community needs. I wanted to understand how to be an effective leader in a sector that often faces competing needs and limited resources, as well as how to manage with efficiency while maintaining a supportive and healthy work environment.

A long-term goal is an C-suite position at an organization that promotes community, equity and justice.

Another goal was to understand how to transition an underperforming organization to high-performing.

The goal of the USM Muskie School of Public Service’s Master’s in Policy, Planning, and Management program is to educate students to:

- Comprehend the fundamentals of public policy, planning, and management.

- Identify and describe problems and solutions from diverse political, economic, and ethical perspectives.

- Evaluate and synthesize problems and solutions quantitatively and qualitatively.

- Design solutions and implementation strategies for organizations and communities.

- Evaluate approaches to public, private, and non-profit organizational leadership and management.

- Articulate strategies to engage and facilitate civic discourse, community participation, and public-private cooperation.

- Communicate clearly, orally, graphically, and in writing, to inform, manage, and persuade.

Professional Resume

Artifacts of Work

Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series

The Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series grew out of a desire to hear more diverse perspectives on matters of leadership and public policy, as well as personal reflection following PPM 615 Organizational Leadership on my role as a leader within the Muskie student body. The series was designed to explore how race, gender, sexual orientation, gender expression, colonization, etc. intersect with public policy and policymaking. Requests went out to active policymakers with experience working on these issues or who hold identities connected to these issues. They were invited to join MPPM students for discussions on their topic of expertise. Food was provided with funds from the USM Intercultural and Diversity Advisory Council.

RPC Events:

- February 20, 2019 — Maine Secretary of State Matt Dunlap spoke about his role on the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- March 13, 2019 — Donna Loring, Senior Advisor on Tribal Affairs, spoke about the position of Native Tribes in Maine.

- March 25, 2019 — Deqa Dhalac, South Portland city councilor, spoke about her role in municipal government.

- April 1, 2019 — Lisa Bunker, transgender N.H. legislator, spoke about her experience as state lawmaker.

- April 15, 2019 — Rachel Talbot Ross, Maine legislator, spoke about racial justice and the Maine legislative process.

Every event included a brief introduction, 10 to 15 minutes for opening remarks, then a 1.5 hour discussion. Speakers received a small gift as thanks, and students were invited to fill out surveys at the close. Series aims included:

- Building connections between Muskie students and sitting policymakers

- Expanding the range of perspectives available to MPPM students

- Considering the impacts of colonialism and structural racism

- Exploring and discussing the role public policy plays in marginalization and oppression

- Learning about current efforts to undo historical policy failures

- Preventing future policy failures

My role: I was the principal architect of the RPC series, designing the format, recruiting speakers, scheduling rooms, conducting student outreach, and at times moderating discussions. I worked alongside several other MPPM students, engaging my leadership and volunteer management skills as well as my project management skills. The series grew directly from lessons learned in PPM 615 Organizational Leadership, and the final assignment (see below) of the course.

This critical analysis informed not only the launch of the Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series, but also every subsequent effort documented in this portfolio. PPM 615 Organizational Leadership forced me to consider my interest in assuming leadership roles within values-driven organizations, and also to reflect on how to do that with openness and sensitivity to diverse perspectives. That reflection informed all of my subsequent graduate work and university involvement.

IDAC Student Fellow Letter to University Leadership

On June 14, 2019, USM hired a tenure-track professor to Educational Leadership who in their last professional role was accused of racial discrimination. At the time of the hire, two investigations into the allegations — one at the Maine Human Rights Commission and one commissioned by the RSU21 school district, where the professor had served as a senior administrator — remained open.

Upon learning of the hire, I organized the Student Fellows of the USM Intercultural and Diversity Advisory Council from the previous academic year to submit a letter (see below) outlining student concerns about the hire, as well as the processes that allowed for the selection of such a candidate. The letter went to USM’s senior leadership, with a request that the job offer be put on hold until the investigations cleared the candidate of any wrongdoing.

The letter, submitted on June 20, 2019, led to a series of meetings with USM leadership:

- July 1 — Meeting with USM Provost

- July 17 — Meeting with USM Provost

- July 26 — Meeting with USM President and Provost

- August 15 — Meeting with USM President, Provost, Dean of the College of Management and Human Services, and the Hiring Committee from the Educational Leadership Department

Over the course of these meetings the students (which included undergraduates, graduate and PhD candidates) argued USM failed to live up to its promise to provide a safe and inclusive learning atmosphere when it hired a candidate facing unresolved racial discrimination allegations. The initial pressure forced a public acknowledgement by the USM Provost, resulting in press coverage. One month later USM President Glenn Cummings announced a 10th institutional goal focused on “equity and justice.”

My role: I took the lead position in this advocacy effort, both crafting the letter that outlined the student position and arguing that position in multiple meetings with administrators. I wrote the letter, organized all meetings with leadership, recruited students to attend, led pre- and post-meeting strategy discussions, and maintained constant communication with both students and USM leadership from mid-June until the start of the academic year, applying constant pressure to university administrators to live up to USM’s professed institutional values.

This work grew directly out of a study I conducted in PPM 560 Crisis and Risk Management, an in-depth examination of the RSU21 school district racism crisis (see below). This background research served as a critical foundation for the student position. Over the course of the summer the ongoing discussions made it clear that students had a more accurate understanding of the situation at RSU21 and than did university officials. Over the course of this campaign I exercised not only leadership, communication and advocacy skills, but also facilitation and negotiation skills. Tense discussions unfolded over several months, requiring delicacy and nuance to move through. Responsibility for that fell primarily to me, even among senior university administrators.

Letter-to-the-Editor in the Portland Press Herald

At the close of Summer 2019, USM leadership remained unmoved by student advocacy on the issue of the recent Educational Leadership hire. While willing to acknowledge a need for broad-based institutional reflection, administrators were unwilling to reconsider any specific decisions.

Around the same time, the Boston Globe ran a prominent story on the failure of one Maine public high school, Edward Little High School in Auburn, to support its non-white students. Following the Globe coverage, the Portland Press Herald did its own series of stories about Edward Little High School, and also wrote an editorial about the need for all Maine schools to do better on issues of race and equity.

Recognizing the limited response from USM leadership to student concerns, I used the Press Herald editorial as a launchpoint for a letter-to-the-editor that critiqued USM’s place in the cycle of ongoing racial discrimination. My letter (see below) pointed out that the recently hired candidate had been educated at USM, and then in a professional role failed to recognize the racial nature of incidents occurring under their leadership. This was not an individual failing, my letter argued, but an institutional one, and so long as USM leads training of K-12 school administrators around the region, issues like those at Edward Little High School are bound to continue.

The Press Herald published the letter on September 6, the same day as the first USM Faculty Senate meeting of the Fall 2019 semester. The letter became an emergency agenda item for consideration. The Provost emailed me after the meeting:

“I thought you would be glad to know that your letter was the catalyst for a tough, honest, and productive conversation about racism, anti-racism, faculty searches, and education at Faculty Senate. It felt like the beginning of a new era: I do not recall such a challenging and progressive conversation in that body in my 17 years at USM.”

My role: The letter was an outgrowth of the leadership and advocacy work I had committed to over the summer, paired with a clear window of opportunity. The week previous USM leadership had told our group the issue was settled, and the hire would stand. I saw the PPH editorial as an opportunity to force a larger conversation outside the confines of the USM institutional structure. I recognized as a student I had few options remaining to force further consideration of the matter within that structure, but that avenues outside the university remained open. This realization was the result of classroom discussions about how media influences power in PPM 560 Crisis and Risk Management, and discussions of the Adaptive Change Model in PPM 615 Organizational Leadership. These helped me see the opportunity to leverage public pressure as a catalyst for systemic change.

At this same time I was holding in-person meetings with individual members of the hiring committee, as well as the senior administrators, to reiterate what about the situation represented an institutional failure. These discussions further developed my negotiation and relationship-building skills. I was scheduled to hold a similar meeting with the professor named in the letter, but upon the publication the professor cancelled. That meeting was ultimately rescheduled, and happened several weeks later. It was productive, but reached no resolution.

AntiracistUSM.org and Student Organizing/Support

Following the incidents of Summer 2019 and the publication of the letter-to-the-editor, USM students with marginalized identities not connected to our earlier work started to seek me out. USM had vacant two critical student support positions at the Student Diversity Centers, and many non-white students were feeling ignored by the university. In highlighting incidents of institutional racism, I became someone these frustrated and alienated students would seek out.

Recognizing a gap in student support structures, I launched AntiracistUSM.org to educate the USM community on the events of the summer and serve as a virtual meeting place for students feeling disconnected and frustrated. I then led a group of students to organize bi-weekly meetings to provide an in-person venue where students could voice frustrations and find support.

The website caught the attention of senior university administrators, who suggested it might serve as a portal for all university efforts around antiracism work.

My role: I designed, built and launched the website, crafting all written content, visuals, etc. The content was crafted on the Adaptive Change Model studied in PPM 615 Organizational Leadership, designed to highlight discrepancies between USM’s actions and stated core values. Ongoing maintenance, upkeep and operation of the site was later turned over to a student volunteer.

I also organized and co-led the initial bi-weekly student meetings. Those too have since been handed to a volunteer. This project was a practice in advocacy and communication, as well as organization and leadership. The connections fosters proved fruitful: We were able to get an undergraduate student with significant grievances around racism an audience with the UMaine System Chancellor. That student relationship was built through AntiracistUSM.org.

Richard Rothstein “Color of Law” Lecture

In Spring 2019 PPM 612 Sustainable Communities, the book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America kept coming up in classroom discussion. The book documents how American segregation came about not as a result of decisions by private actors, but was the product of explicit government policy. The class focused on planning and land use, and one enthusiastic student kept referencing the book repeatedly.

When the semester closed, that student notified that me they had reached out to the author, Richard Rothstein. The student asked if I might be able find a way to bring Rothstein to USM.

Six months later, on December 5, 2019, I introduced Rothstein to several hundred attendees at Hannaford Hall:

My role: When the interested student approached me, they had learned it would cost between $10,000-$15,000 to bring Rothstein to USM. Armed with that information, I went to find the money. After approaching a number of university departments, I partnered with the Osher Map Library’s Mattson-New York Times Lecture and the Annual W.E.B. Du Bois Lecture on Race and Democracy. Once funding was secured, I moved on to organizing the event, coordinating with the two professors in charge of each lecture series. I also coordinated with the USM Intercultural and Diversity Advisory Council on the purchase of 100 copies of the book to stock the USM library and be made available to interested readers. Lastly, I coordinated with representatives of the American Planning Association to allow Maine town and city planners to earn continuing educational credits for attending the lecture.

This project honed resource procurement skills, organizational and project management skills, as well as my public speaking and presentation skills. It also allowed my to practice building partnerships to maximize organizational efficiency — if Rothstein only spoke to students, the full value of his lecture would have been lost. The partnership with the American Planning Association created additional community value at no added cost.

USM President’s Email Letter Regarding Campus Incident

Over the Fall 2019 Thanksgiving Break, an incident occurred on a social media account indirectly affiliated with USM: Someone posted a photo of a white USM student posing next to a racial slur spray-painted on an exterior building wall. The student was smiling with their hands held as if to showcase the slur.

The incident sparked a backlash on social media, as well as concerns about student safety. An undergraduate from AntiracistUSM.org reached out to ask if I would advocate for marginalized students, so I reached out to Student Affairs, ultimately assisting them in writing a response email that went out to the full USM community.

Following the holiday break, USM leadership asked if I would draft a more complete communication, this time to come from USM President Glenn Cummings. After several back-and-forth emails with a variety of university staff, faculty and administrators, I wrote the email (see below) that went out on December 12, 2019, that acknowledged the incident, the historical context it exists within, and recommitting USM to face difficult conversations about racism, marginalization and oppression directly.

My role: I drafted this communication with minimal feedback or revision from USM leadership or staff, relying on my experience working with USM students with marginalized identities and the USM Intercultural and Diversity Advisory Council. It went out almost exactly as I’d written it, save the addition of a line thanking both me and IDAC co-chair Professor Rebecca Nisetich, who reviewed my work.

In writing this email, I relied heavily upon concepts explored in PPM 610 Governance, Democracy, and Policymaking, particularly the inherent tensions present in a democracy, and “democracy” as a set of systems and values as opposed to a governing structure. These were critical ideas that informed both the email and the solution I proposed within it. I also drew from lesson in PPM 615 Organizational Leadership (and later in PPM531 Measuring Performance in the Public and Nonprofit Sectors, though I’d not yet had that course) about how mission, vision and values can be leveraged to determine a strategic path forward.

This idea of “a democratic space for difficult conversations” came directly from PPM 610 Governance, Democracy, and Policymaking, and is reflected in my final assignment for the course (below).

This was another advocacy project — I used the opportunity to further student concerns and spell out a commitment for the university to engage in difficult conversations — but it also hinged upon months of relationship-building. Despite having publicly criticized USM in the newspaper a few months prior and launching a website that criticized the institution’s ability to live its values, I maintained sufficient trust among both USM undergraduates with marginalized identities and university leadership to serve as a trusted advisor to both. This ability to navigate complex organizational realities is exactly the skillset I’d hoped to build at Muskie.

Anti-Racist Practice Group

At the close of summer 2019, a handful of USM faculty and staff, along with concerned members of the Greater Portland community, decided to convene to consider strategies to influence USM institutional choices that perpetuate systemic racism. Group membership included but was not exclusively individuals concerned with the USM hiring of a professor in June 2019.

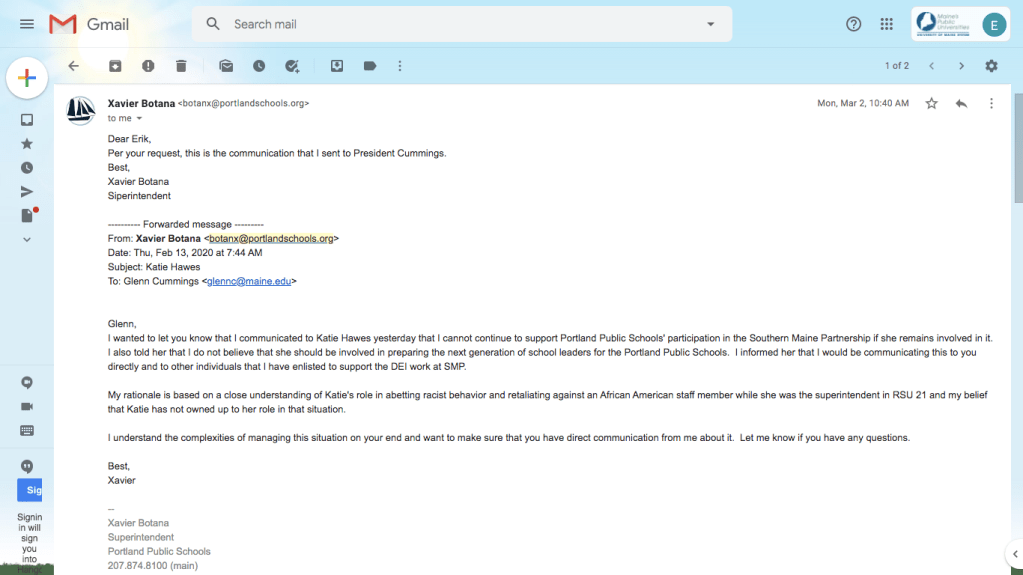

Initial meetings included study of how racism operates, as well as relationship- and trust-building. Members then coordinated on plans to pressure USM into renewed consideration of institutional failings. Anti-Racist Practice Group members coordinated successfully to raise public pressure regarding the USM hire via the Portland school board, eventually convincing the Portland Public Schools to publicly end a professional relationship with the university until USM’s equity positions improved.

My Role: As one of the critical figures organizing pressure on USM leadership around institutional racism failures, I was involved in the Anti-Racist Practice Group from its launch, aiding with the design, coordination, management and ongoing operation of the group. I served as critical support strategist for the lead organizers, and was a stand-in facilitator/group leader during biweekly meetings when the lead organizers could not attend. I was also the primary coordinator of external group actions, leveraging group relationships at key moments to impact institutional decisions. For instance, I alerted the group to the incident that provided the window to put pressure on Portland Public Schools. I then crafted the public statement presented to Portland Public Schools by a Portland school board member. This coordinated action led Portland Public Schools to look deeper into USM’s equity record, which put further public pressure on USM to reconsider its June 2019 hire. I also managed the media strategy that led to renewed news stories about the June hire, including the above story, which grew out a request I made via Maine’s Freedom of Access Act for Portland Public Schools email records:

This group served to further pressure USM long after student concerns were put aside. It was only after Portland Public Schools raised concerns that USM leadership changed how it was approaching a situation students had raised months before. I was the only student member of the Anti-Racist Practice Group, and yet I served an important leadership role, both in its initial launch and later in its actions. This was critical experience in advocacy, volunteer coordination, and in practicing both leadership and followership. Unlike most other groups outlined in this portfolio, I did not fill the primary role of the Anti-Racist Practice Group, but instead was a key team member that helped determine strategy and ensure the success of group actions.

USM Common Read

In late Summer 2019, USM announced a campus-wide Common Read, with the focus tied to the newly announced USM Goal 10 on “Equity and Justice.” I was asked by university leadership to be part of the ad hoc book selection committee, which ultimately chose Ibram Kendi’s How To Be An Antiracist as a text. The university purchased roughly 5,000 copies that were made available to students, staff and others in the USM community for free.

The book purchase, however, did not outline a structure for how the Common Read would be used, or offer guidance for how to discuss such a charged topic with sensitivity and nuance. After several months of limited structure, university leadership turned to a handful of faculty, staff and students who had led campus efforts on racial equity to help fill in the gaps. That group laid groundwork that would eventually become the USM Common Read website, which supported a series of facilitated discussions run by students, staff and faculty.

My Role: I was one of only two students tapped to take part in the initial Common Read text selection, and one of two students asked to design and build the structure for implementation. The resources that were eventually dedicated to Common Read implementation were a direct result of pressure applied by the work of our student group. The student leader who ultimately took a primary role in creating a Common Read plan was recruited by me in the early stages of student organizing. This recruitment represented a new sort of leadership practice for me: Finding someone else with critical skills I lacked and enlisting their involvement in my project. Previous leadership had largely centered around organizing and did not require specialized skills. This was different. The university ultimately benefitted from this person’s expertise and years of experience. This person had previously tried to find a meaningful opportunity to engage their skills at USM but found limited success. My leadership made optimal use of the individual within the institutional setting, with benefits for the both individual and the institution.

Furthermore, the desire for a race-specific text cannot be understood outside the context of the larger student organizing. The text was a direct response to the issues our group had been highlighting since June 2019. The USM Common Read was an institutional signal that the validity of the problem analysis offered by students was recognized by university leadership, even if they were unwilling to address student concerns directly. It further illustrated the logic of student calls that institutional resources must be dedicated to combating racism, not just new goals announced.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly curtailed the number of Common Read facilitated groups that met, but some did convene. I led one Common Read group and was a participant in another, both via Zoom. In both groups participants found so much value in the discussions they opted to continue meeting even after all scheduled sessions had concluded.

Conferences, Talks, Workshops, Etc.

Conferences

12th Annual Camden Conference: Is This China’s Century, February 22-24, 2019

2019 Universities Fighting World Hunger Summit — Fighting Hunger in a World of Plenty: Shifting Power and Taking Action, March 15-16, 2019. Conference presenter: Contributing Factors Leading to the Growth of Portland’s Seafood Scene, by Eric Day, Erik Eisele and Katherine Klibansky of USM’s Muskie School of Public Service

15th Annual Black Policy Conference at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government: Affirming Blackness — Protest, Passion & Policy, April 5-7, 2019

13th Annual Camden Conference — The Media Revolution: Changing the World, February 21-23, 2020

Talks

Betta Ehrenfeld Public Policy Forum: Maria Echaveste, former White House Deputy Chief of Staff — The Fair Labor Standards Act: In the New Economy, How Do We Honor and Fulfill Its Original Purpose? September 27, 2018

USM 3rd Annual W.E.B. DuBois Lecture: Nadine Strossen, professor at New York Law School — Why We Should Promote Racial Justice (And Other Good Causes) Through Free Speech, Not Censorship, October 17, 2018

Lawrence Lessig, professor at Harvard Law School — The Battle For Rank Choice Voting, October 25, 2018

Maine Initiatives: Maulian Dana, Tribal Ambassador of the Penobscot Nation, and Bree Newsome, racial justice activist — A Candid Discussion About Activism and Identity, March 29, 2019

World Affairs Council of Maine: Susan Rice, Former U.S. Ambassador — A Conversation on Race, Family, Leadership, and Diplomacy, October 25, 2019

Osher Map Library Mattson-New York Times Lecture and 4th Annual W.E.B. DuBois Lecture: Richard Rothstein, Distinguished Fellow of the Economic Policy Institute — The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, December 5, 2019

Osher Map Library: Roger Paul and Newell Lewey, Passamaquoddy language teachers and linguists — Peskotomuhkatik yut: This is Passamaquoddy Territory, January 23, 2020

Muskie Lunch & Learn Research Hour: Rosemary Mosher, GIS Manager for the City of Auburn — Open Data for Municipal Engagement, February 20, 2020

Black History in Maine: Daniel Minter, artist, and Myron Beasley, Associate Professor of American Studies at Bates College — At the Mouth of the River: Retelling the Malaga Island Story and Against the Master Narrative: Tall Tales and Maine’s Bicentennial, February 21, 2020

Osher Map Library: James Francis, Jr., Director of the Office of Historic and Cultural Preservation at the Penobscot Nation — Penobscot Sense of Place: The Relationship Between Land, Language, and Penobscot Culture, February 26, 2020

Workshops

Wabanki-REACH: Mapping Workshop, designed for non-Native people, introduces concepts of white privilege and decolonization with a brief history of U.S. government relationships with Native People, December 11, 2018

Racial Equity Institute: Phase 1 Racial Equity Workshop, designed to develop the capacity of participants to better understand racism in its institutional and structural forms, January 22-23, 2019

Racial Equity Institute: Phase 1 Racial Equity Workshop, participated as workshop reviewer, August 20-21, 2019

USM Common Read: How To Be An Antiracist Facilitator Training, designed to prepare participants to serve as facilitators of discussions on the USM Common Read, February 21, 2020

Other

Graduate Assistant, USM Office of Service-Learning and Volunteering, 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 Academic Years

Student Fellow, USM Intercultural and Diversity Advisory Council, 2018-2019 Academic Year

Site Leader, 10th Annual USM Husky Day of Service, April 12, 2019

Representative, Muskie Student Organization, 2019-2020 Academic Year

Research Assistant, USM Cutler Institute Justice Policy Statistical Analysis Center, Hate & Bias Crime Reporting research project, 2019-2020 Academic Year

Reflective Essay

LEADERSHIP PRACTICE: Embracing Complexity

I came to Muskie looking to build concrete skills for nonprofit leadership. My experience working with nonprofits had made clear that many leaders/managers lack a toolkit for balancing all the various organizational needs — people, resources, finances, time, etc. — in an efficient and effective manner. I wanted to lead, but without subjecting those under my leadership to such shortcomings.

In my first full-time semester, however, PPM 615 Organizational Leadership pushed me to think more deeply about leadership and the role I was seeking. The class asked a series of provocative questions: What does it mean to be a leader? How does a leader lead, as opposed to manage? How does a leader navigate setbacks and challenges? How do they negotiate an evolving sector, an evolving market, and an evolving world? How can they successfully hold everything together? When things grow dire, how can they adapt and grow rather than fall to pieces?

These questions struck me. I had come to Muskie looking for tools, but this conversation was more profound. I recognized that to be the leader I wanted to be I needed not only to have the skills to make a budget, craft a strategic plan and measure performance, but I also had to learn to listen to criticism, grow from failure, and change with conditions. The first set of skills seemed far simpler than the second. To be the leader I aspired to be, I would have to stretch beyond my comfort. Such reaching, I knew, requires practice.

The following semester I decided to take my first concerted stab at complex leadership when I launched the Muskie Race & Policy Conversation Series. It started with an idea, and with a few friends I fired off a bunch of emails. Those emails grew into a speaking series. It was not without hiccups — the first guest was the Maine Secretary of State, a white man, which drew immediate criticism — but it offered a chance to take risks, and to learn. I took the criticism of our first guest (which was well founded) and other feedback as opportunity for reflection. I let it fuel growth and improvement, just as PPM 615 had suggested.

That first stab at a leadership project proved a success, and it quickly spiraled into more work on race, colonization, marginalization and oppression. I did not aim for these issues to become the focus of my USM work, but in looking for leadership opportunities these were where vacuums appeared. Openings kept emerging, and each new effort forced me to take new risks — being a cis-gender straight white man engaging in discussions about misogyny, racial hierarchy and colonization is rife with opportunities for mistakes. But also there were many chances for reflection and learning. I soaked up everything I could, embracing stumbles and seeking out new avenues for growth. Along the way I found myself enlisting others, encouraging larger institutional reflection, and using my role as “student” to feed policy reform.

Every step of this was an outgrowth of my MPPM work. PPM 615 hatched the idea, and I kept finding ways to develop it and explore further. With few models of white men leading such work to draw on, I was forced to consider carefully the impact of both my leadership choices and style. I reflected often, and pondered those moments where my actions failed to align with my values. That internal process forced me to look for feedback, support, and partners, and each strengthened my efforts. I even reached out to those deeply critical of the work I was doing, including professors who were threatened and at times actively hostile. We would meet over coffee, forcing me to closely consider my approach. This allowed every criticism an audience, forcing me not to shy away from difficult conversations. All of it fed deeper reflection.

Through this process, over the course of the last year I became a leading voice on equity at USM. The university president and multiple members of the cabinet turned to me and the team I assembled in moments of crisis. Our team helped USM build a capacity for deep internal reflection on how the institution handles issues of race and oppression. We forced this reflection despite a position of limited power within the university hierarchy. We leveraged every opportunity available to us, and our work made an impact. Every part of that success is rooted in my Muskie experience. This process started with PPM 615, but it was informed by multiple MPPM courses. This experience taught me much of what I came to Muskie to learn: If MPPM students are to lead Maine in the 21st Century, then we must become proficient in complexity. To chart a new path, we must take up the mantle of leadership, including its risks. This means chancing failure, public failure. But this is also a chance to enact transformational change.

I did not start the Race & Policy Conversation Series with such goals in mind. I did not understand the scale of the challenge I set for myself at the time. I simply followed opportunities where they led. I am grateful for the learning and growth I experienced at USM and the Muskie School. It was a lesson in embracing complexity and learning to move fluidly within it. Today, having weathered contentious disputes with university leaders, taken public stances on issues of equity and justice, and having pushed an institution to live closer to its values, I understand more concretely what it means to take on the risk of leadership. I’m grateful for that experience.

And along the way I got to practice budgeting, advocacy, public speaking, communication, volunteer management, project management, systems creation, resource allocation, strategic planning and a host of the other skills I originally came to Muskie to learn. These are critical for everyday management. But management is only part of what is required to lead. A penchant for continuous exploration, learning and growth is critical. A leader with the humility to recognize they still have much to discover is a leader ready to adapt to the next unforeseen challenge.

That was not what I set out to learn at Muskie, but it has been deeply reinforced. I’m grateful for that experience, and I suspect that I will be back. If I hope to be a good leader/manager, after all, there is always more to learn.