Sometimes the economy and the environment are at odds.

Sometimes the economy and the environment are at odds.

In recent weeks I’ve been reading a lot about plastic, and plastics in the ocean in particular.

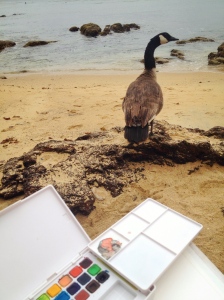

It started in April with a stop at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Wandering the exhibits I came across a pair of displays in the Sant Ocean Hall that caught my attention: two piles of trash. One was pulled from the stomach of a seabird, the other from the stomach of a whale. In each pile were hundreds of scraps—pieces of bags, bottle caps and boat parts—almost all of them plastic. Both animals died as a result of their ingestion choices. Plastics look bright and shiny, similar enough to edible tidbits these creatures have eaten for generations to be deadly. So they gobble it up. The result is a belly full of trash.

That was the first thing that got me thinking about plastic. Then I stumbled upon a “say no to straws” campaign highlighting the amount of plastic used each day for the completely arbitrary task of getting our drinks out of our glasses and into our mouths. It seemed absurd: like there isn’t another way to drink a drink? Is that really what we are doing, filling our oceans with garbage in exchange for saving us the trouble of lifting our glasses?

After a bit more research and a few conversations with friends I learned about this initiative:

Apparently the answer is yes, that is exactly what we are doing. Plastic is everywhere. EVERYWHERE. In the ocean, ground up into little bits so small we can’t even see them, rolling among the waves.

That is plastic in the environment.

Then there is plastic in the economy. This morning a news piece from Marketplace.org called “The Next Global Glut: Plastics” popped up on my news feed. The gist is this: with crude oil prices at record lows production of oil-derived goods like plastic are going to increase.

Several new petrochemical plants are being developed, especially around Houston and Louisiana. Vafiadis said the high output from the natural gas industry in the U.S. makes it financially feasible for companies to spend billions of dollars in new plants.

“There’s enough natural resources available to make the majority of the projects that are being considered today viable,” Vafiadis said.

As new plants come online, global plastic output will swell. IHS expects that more than 24 million metric tons of new production capacity of polyethylene alone will be added to the market by 2020. About a third of that new capacity will come from the U.S. and will come online within the next few years.

Not mentioned in the story is with increased production comes increased disposal. The giant pile of trash already swirling in ocean will grow.

The environment and the economy—when it comes to plastics there seem to be two distinct conversations: one about growth, the other about impact. Watching these conversations unfold in tandem and without intersection is like watching someone with multiple personality disorder argue with themselves. It’s two halves of the brain unable to connect directly. There are questions of demand, but also of impact. Where is that, the complete conversation, supposed to live?